As I rounded the corner of my house on Friday, the UPS driver hopped out of his truck -- smiling and waving at me.

(For YEARS, he delivered diapers to our door at a staggering rate. He pushed them inside the front door for me, and once, when I clearly had my hands more than full with 4-week-old twins and a 2-year-old, he offered to unbox them for me. We rewarded him with generous gift cards at the time, and while his deliveries have dropped off dramatically over the years, he still pulls up with a smile and a bounce in his step.)

I am sure I looked puzzled, because I was not expecting anything.

Which was silly, actually, for the clinical trial coordinator had sent me an e-mail on Thursday telling me that she would be "overnighting" me a "2-day supply of study meds," which, of course, meant that I should very much have been expecting some sort of delivery at some point in the day on Friday.

No offense to UPS, but IF had been expecting a delivery driver, I would have been looking for a FedEx truck (in my mind, "overnight" and FedEx are nearly interchangeable words...).

But, in all honesty, I had already forgotten about the delivery I should have been expecting on Friday. To those who don't know me, this might make some question my commitment to the clinical trial, but let me assure anyone who might be concerned that while I am highly ambivalent about this whole journey, I am also absolutely committed.

While a huge part of me is still very much struggling with the fears I have that are associated with participating in something (anything) that is risky (I do, after all, have a husband and three children and a private practice as a social worker...and all sorts of volunteer activities), I still absolutely and completely understand how important it is that subjects in clinical trials remain in the clinical trial for the duration of it whenever possible. Whatever happens, I'm going to see this through.

After the UPS driver left, I looked at the return address on the package. Ahhh. Yes. Of course.

Right.

The Study Drug.

I put the package on the marble table in our foyer. It is the table for incoming and outgoing mail...and anything else that needs to go with us when we leave the house next. Sometimes it is VERY cluttered, but on Friday, the table was empty.

Except for the package.

I left the package there. I knew what was in it, and I knew that I did not need it until Sunday.

I had work to do.

I went back to my home office, but the package drew me down the stairs, back to the marble table.

What if there was something else in the package?

What if there was a note asking me to do something?

What if the study drug required special handling?

What if I had questions?

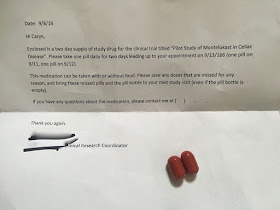

I opened the package and found a note with simple instructions, and a prescription bottle with my name labeled "Montelukast or Placebo (IRB 15-1413) 10 mg" with a big yellow sticker that read "FOR INVESTIGATIONAL USE ONLY."

Curious, I opened the bottle.

I poured the (two) pills into my hand.

One dose for Sunday, one dose for Monday.

(Gluten Challenge on Tuesday.)

The pills were sort of silly looking -- big, fat, puffy...RED.

I texted a picture to a friend who responded that they looked like "horse pills."

(She's the kind of person who can say this from experience, which gave me pause.)

This morning, I took that first pill.

But first, I hefted it in my hand.

It felt like a pretty regular pill.

Except that it was big.

And then I shook it.

Something rattled around inside.

Very interesting.

It wasn't until after I swallowed it that I realized I could have opened it.

But, I wouldn't have.

And I won't.

Because...curiosity killed the cat...and I don't want any sort of bad karma, even though I know full well that what is in the pill is said and done, and beyond my control.

Whatever happens, I'm going to see this through.

Since my current adventure has little to do with Eating Peanut, but it turns out lots of readers want to follow along, I started Eating Gluten last night. If you want to follow along, you can find it at: Eating Gluten.

In the spring of 2011, I was diagnosed with Celiac Disease. The diagnosis was not obvious, as I did not have any of the more commonly known symptoms -- no gastrointestinal distress, no chronic diarrhea, no bloating, no vomiting. (I now know these are just a few of the symptoms, and that these symptoms are actually the types of symptoms seen in children, not adults.)

The diagnosis followed a lot of tests, several of which considered things far more serious than Celiac Disease (think cardiac disease, blood borne cancers and more...).

I was honestly relieved by the diagnosis -- which was suggested by a blood test and confirmed with the "Gold Standard" of diagnostics -- an upper endoscopy to look for inflammation and to take a number of biopsies of my small intestines followed by three months of gluten-avoidance and then a second upper endoscopy to confirm evidence of healing.

I know there are some who will doubt me when I say that I was not even particularly daunted by the diagnosis, but I wasn't. Having mostly mastered the art of managing Susan's food allergies (and having become accustomed to spending a lot of my time assuring that there was not even the possibility of a trace amount of peanut in anything she might eat), Celiac Disease -- avoiding gluten -- seemed like a relatively manageable thing to me. And it was a lot better than some of the other things doctors had considered along the way to the diagnosis.

I still remember one friend who reacted with horror -- telling me that I would never be able to avoid gluten on top of being vegetarian (by choice) and keeping a strictly nut-free and very-limited-soy household.

I remember another friend who mourned the end of my baking (a hobby I loved). I remember that friend wondering aloud if I could get away with "cheating." When I gave her a funny look, she explained that she thought I might be able to get away with "cheating" since I had never had any clear symptoms of Celiac Disease. I remember patiently explaining to her that if living gluten-free would rid me of my debilitating fatigue, the threat of fainting every time I stood up and the frighteningly regular irregular heartbeats I had grown accustomed to, there was NO way I would ever cheat.

And I meant it.

I have never "cheated" on my gluten-free diet.

(That's not to say I haven't been "gluten-ed," for I have. And that's no fun, for sure.)

But, why would I cheat?

What message would THAT send to Susan, for whom a "cheat" could result in a life-ending anaphylactic reaction.

I never felt that Susan needed me as an example, but once I found myself in a position where I had to scrupulously check and sometimes avoid foods for my own health, there was no way I was going to do anything but exercise extreme caution when it came to food.

Despite my friends' dire predictions, avoiding gluten in our mostly-free-of-prepackaged foods household was not really all that hard.

Despite my children's fears, I did not make our whole household gluten-free. I found suitable substitutions for some foods and simply live without others. (I recognize that I am fortunate to have been diagnosed with Celiac Disease in 2011 instead of 2001 or even 1991...as times have changed, for sure.) I gave up my baking hobby and stopped regularly baking for others, although I never stopped baking for Susan. As the years have passed, I have begun baking some, although I try to limit my use of flour, as I have come to understand how it swirls through one's kitchen, microscopic traces of it lingering in the air, hanging on the drawer handles and cabinet pulls, "dirtying" the countertops that look clean.

Despite my friends' certainty that my life was going to change for the worse, I embraced my new gluten-free lifestyle, made healthy choices and moved on. Feeling good, healthy -- strong -- was all the reward I needed for my efforts.

I can honestly say that within a few months, I got to the point that I really didn't think that much about life with Celiac Disease. It was just a part of who I was, and how I ate.

Celiac Disease did not define me.

Celiac Disease did not limit me.

I did not feel in some way like I had somehow brought Celiac Disease upon myself.

And despite some people's certainty, I never felt that there was a clear connection between the fact that I had Celiac Disease and Susan's food allergies.

I always carried things I could eat with me, but, again -- that was no different than what I had always done for Susan.

I did not worry at the diagnosis, wondering why I had Celiac Disease...I simply lived with it.

Life went on.

And really, life was just fine.

So -- when I got an e-mail from the University of Chicago earlier this summer, seeking volunteers for a clinical trial for Celiac Disease -- studying the efficacy of Singular (a drug I have come to know well -- and love -- because of it's role in Susan's OIT) on tolerance of gluten by those with biopsy-diagnosed Celiac Disease, I paused.

I thought about it.

I thought some more about it.

I started to delete the e-mail.

I am busy.

My husband is still recovering from his illness earlier this year.

Susan is still undergoing OIT for her peanut allergy.

I told myself I did not need to take anything else on.

And yet, I didn't delete the e-mail, but...I also did not respond immediately.

And then I texted Susan, who was at the skating rink:

Hey -- think I should do a clinical trial for Celiac Disease? It is a double-blinded study with a 1:3 chance of being asked to eat gluten (bread) while receiving placebo...

Susan: I think you should do it!

Somehow...I knew you would say that!

And then I texted a friend, who said essentially the same thing. And then I took a very long walk and thought about it...and when I got back, I sent an e-mail.

Over the next few days, I exchanged several e-mails with the clinical trial coordinator and had a lengthy conversation with her. We talked about blood draws, upper endoscopies, fecal samples, and gluten challenges. We talked about Singular and the placebo. We talked about commitment.

Commitment.

It is a big word, and an even bigger responsibility.

The clinical trial coordinator was clearly trying to assess my level of commitment. And I think she liked what she heard when I shared a bit about Susan's clinical trial experience with her.

I know first-hand what placebo looks like in a clinical trial.

I understand all too well how what a protocol says might not actually be the way things look in the end.

I understand about extra visits and unexpected blood draws.

I understand about the unknown.

The clinical trial coordinator e-mailed me the study protocol. I reviewed it. My husband reviewed it. I signed it, scanned it, and e-mailed it back. A few days later, I executed a release allowing the doctors at the University of Chicago Medical Center to obtain the medical records pertaining to my original diagnosis.

(For those who are curious, this clinical trial is for research purposes only. When I get done, I will go back to my gluten-free diet, and hope that what the researchers learn as the result of this clinical trial will move them one step closer to a treatment.)

The wheels were in motion...and I was sort of terrified at the prospect.

While I am fully committed to this clinical trial, if I am honest with myself, I will admit that a BIG part of me -- a reallyreallyreally big part of me was hoping that somehow, for some reason, I would not be a good candidate for the clinical trial.

Of course, one reason a clinical trial candidate might be disqualified from this clinical trial (most, I assume, actually) is unrelated health issues.

And I certainly did not want an unrelated health issue to come to light during the course of my evaluation.

And, of course, another reason a clinical trial candidate might be disqualified from this clinical trial is uncontrolled Celiac Disease.

And given my commitment to a gluten-free diet, I certainly did not want to learn that my Celiac Disease was not controlled.

And so, as much as I hoped -- really, reallyreally, truly hoped -- I would not be a good candidate for the clinical trial, at the same time, I also hoped -- really, truly hoped -- that nothing would come to light that would disqualify me from the clinical trial.

Days passed.

Weeks passed.

I thought "phew!"

I thought "I'm not a good candidate based on my original diagnosis."

I thought "I bet they don't have funding yet (been there, done that)."

And then I got an e-mail.

The medical records pertaining to my original diagnosis looked good.

They had funding.

They were ready to go.

Could I come in mid-to late August for a blood draw?

Could they tentatively schedule an upper endoscopy for the last week of August?

Ummm.

Sure.

And so I went for that first blood draw.

I was SO nervous -- not about the blood draw, or the protocol review, or the papers I had to sign, or the intake questionnaire.

I was sososo nervous because...I am embarking on something medically unnecessary, with unknown consequences, and an unknown outcome.

I do not have to take this risk.

It isn't that I am afraid I will receive the placebo -- I have no control over that. My clinical trial identification number was assigned long ago, and attached to it was the randomization for the clinical trial. While I do not know whether I will be given Singular or the placebo, that part of it is already done.

I am nervous because I do not have to take this risk.

The wheels have rolled quickly since that first blood draw.

Lab results.

Check.

Fecal sample.

Check.

(And can I just say -- best to get such a thing done while all member's of one's household are sleeping or out?!?)

Upper endoscopy.

Check.

(And if I was nervous about the blood draw, I was positively terrified about the upper endoscopy -- an easy, simple procedure I had already undergone twice.)

When the nurse asked why I was so nervous, I explained: I am nervous because I do not have to take this risk.

She heard me, and said something about how she was certain I would be fine, because I am not doing this for myself.

Of course, everything was fine that day.

And everything IS fine.

So fine, in fact, that I've been scheduled for my first gluten challenge.

Yep.

Susan grinned when I told her.

I grinned back, but deep down inside I felt (and feel, even as I type this) fear.

I do not have to take this risk.

I am nervous because I do not have to take this risk.

But this is a risk I am going to take -- for Susan, and for everyone in this world who has to think about absolutely everything they put in their mouth.